As the Tren de Aragua gang faces deportation under President Trump’s invocation of the Alien Enemies Act of 1798—a law thrice wielded in our history to expel foreign threats—Americans confront a chilling echo of colonial tyranny, where rogue judges and a corrupt Uniparty of Democrats and RINOs prop up a globalist regime, deaf to the People’s will.

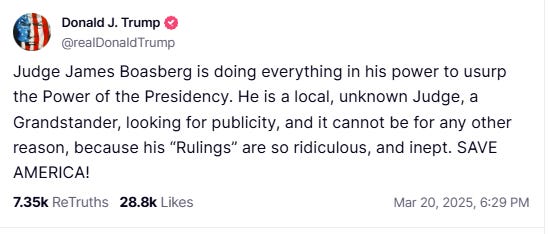

President Donald J. Trump, 20 March 2025, 6:29PM EST, Truth Social, https://truthsocial.com/@realDonaldTrump/posts/114197120302143482

This radical judiciary, laced with corruption and unaccountable overreach, mirrors the Crown’s lackeys who once trampled colonial rights, quartering foreign troops in homes and bending justice to imperial whims—provoking the Founding Fathers to spill blood and treasure to cast off those brutal boots for liberty’s sake. Through the prism of that hard-won peace, this discussion will expose the risks these modern usurpations pose to our Constitutional Republic, illuminating how the Federalist Papers’ warnings resonate anew in a fight to safeguard freedom from a judiciary teetering on the edge of tyranny.

“The Shot Heard Round The World” A 250th American Revolution Event, 19 April 2025, https://www.lakemurraycountry.com/event/the-shot-event/

Examples of Colonial Era Judges Who Inflamed A Revolution

Why should we, in 2025’s whirlwind of chaos, spare a thought for the rogue judges who inflamed a revolution over two centuries ago—those bewigged lackeys of King George who twisted justice to choke colonial throats? We care because their story is ours: when courts bow to tyrants, quarter foreign boots in our homes, and shred the rights of the governed, they sow the seeds of rebellion—or ruin—patterns the Federalist Papers begged us to heed, lest we repeat them. Ignore this history, and we invite the same judicial tyranny to fester unchecked, turning blind eyes into bound hands as today’s Uniparty and radical benches echo those ancient abuses—prompting the stark examples of judicial treachery and patriotic resistance that follow.

Trial of John Peter Zenger (1735): Though earlier, the case lingered in colonial memory: royal judges sought to punish Zenger for criticizing the governor, only to be thwarted by a jury’s acquittal. The judges’ willingness to silence free speech under Crown pressure alarmed colonists, who saw it as a precedent for judicial overreach. This inspired later demands for press freedom and impartial courts.

Writs of Assistance Cases (1761): Judges like Thomas Hutchinson in Massachusetts upheld writs of assistance, allowing British customs officers to search homes without specific warrants. Colonists saw these rulings as a betrayal of English legal traditions, with judges favoring royal authority over individual rights. James Otis’s fiery opposition to this inspired broader resistance, echoed in the Federalist Papers’ call for balanced governance.

Suppression of Colonial Assemblies (1760s-1770s): Judges often supported royal governors in dissolving elected assemblies that defied British edicts, such as New York’s in 1767 over tax disputes. By siding with the Crown and nullifying legislative rights, these judges alienated colonists who prized representative governance. The Federalist Papers later emphasized separating judicial and executive powers to prevent such abuses.

Enforcement of the Proclamation of 1763: Judges backed the royal decree barring western settlement beyond the Appalachians, ignoring colonial charters and land claims. This frustrated settlers and speculators alike, who saw courts as blocking their natural rights to expand and prosper. The judicial alignment with imperial restrictions over colonial aspirations heightened revolutionary sentiment

Quartering Act Enforcement (1765, 1774): Judges upheld the Quartering Acts, forcing colonists to house and supply British troops, even in peacetime, without their consent. This was seen as a violation of property rights and personal autonomy, with courts dismissing colonial objections as irrelevant. The lack of judicial recourse deepened resentment toward both the Crown and its compliant magistrates.

Admiralty Courts and the Stamp Act (1765): British-appointed judges in Admiralty Courts enforced the Stamp Act without juries, denying colonists their traditional right to trial by peers. These judges, paid by the Crown, consistently ruled in favor of British revenue interests, infuriating colonists who saw them as tools of oppression. This bypass of local legal norms sparked widespread protests and cries of tyranny.

Dissolution of Colonial Courts (1770s): Royal governors, backed by compliant judges, often suspended or dissolved local courts that resisted British policies, replacing them with Crown-controlled tribunals. In Virginia, for instance, this disrupted justice and left colonists at the mercy of biased appointees. Such actions convinced leaders like Madison that judicial power needed constitutional checks.

Judges’ Salaries from the Crown (1773): Parliament mandated that colonial judges’ salaries be paid directly by King George III, not local assemblies, undermining judicial independence. In Massachusetts, Chief Justice Oliver’s acceptance of this payment led the Assembly to declare him "obnoxious," as colonists feared he’d prioritize royal interests over justice. This move inflamed tensions, reinforcing perceptions of judges as royal puppets.

Coercive Acts’ Judicial Overhaul (1774): The Massachusetts Government Act replaced elected judges with royal appointees, stripping colonists of control over their judiciary. These new judges suppressed dissent, such as by jailing protest leaders, acting as extensions of British policy rather than local justice. These blatant power grabs radicalized colonists, who felt their right to self-rule was obliterated.

Administration of Justice Act (1774): This act allowed judges to transfer trials of British officials accused of crimes to England, shielding them from colonial accountability. Colonists viewed this as a blatant miscarriage of justice, with judges enabling imperial impunity rather than upholding local law. It was dubbed the "Murder Act" by Patriots, stoking revolutionary fervor.

Boston Port Bill Enforcement (1774): Judges upheld the Boston Port Bill, which closed the port and crippled the economy, acting under royal orders without local consent. Their enforcement of this punitive measure, bypassing colonial charters, was seen as judicial complicity in economic warfare. This deepened the Founding Fathers’ resolve to curb such unchecked power.

Suspension of Habeas Corpus (1777): During the war, British-appointed judges in occupied areas suspended habeas corpus, allowing indefinite detention without trial for suspected Patriots. Colonists viewed this as a tyrannical erasure of a bedrock English right, with judges acting as enforcers of martial law rather than protectors of liberty. Such actions reinforced the need for a judiciary accountable to the people, not the king.

Political Fuel-Air Explosives Needing Only A Spark To Ignite Revolution

In some colonial-era cases, troops remained relatively disciplined—helping with chores or keeping to themselves—but this was the exception, not the rule. More often, foreign soldiers, far from home and under lax oversight, treated colonial households with disdain, pilfering food, liquor, or belongings under the guise of "requisitioning" for the Crown. Reports from places like Boston in 1768, after troops were quartered to quell unrest, describe drunken brawls, sexual harassment of women, and property damage, with colonists powerless to evict them or seek redress through Crown-friendly courts.

The lack of consent was galling enough, but the troops’ arrogance—acting as deserving occupiers rather than guests—amplified the insult. In New York, resistance to the Quartering Act of 1765 sparked riots partly because soldiers demanded more than the law required, like firewood or bedding, and judges backed them up, leaving colonists footing the bill – even why the beds provided left colonists with none. By 1774, with the updated Quartering Act under the Coercive Acts, the presence of redcoats in private homes became a daily reminder of lost autonomy, fueling the push toward rebellion.

An initial burden like the Quartering Act starts as a grumble-worthy annoyance, but when it’s compounded by usurpations, intrusions, and outright assaults, it festers into something far more volatile. It’s not just the act itself, but the cascading indignities—soldiers overstepping, judges rubber-stamping, and colonists left voiceless—that turn a spark of frustration into a bonfire of rebellion, ready to catch flame from any stray political or social gust.

Colonial Quartering Act of 1765, USHistory.org, 24 March, 1765, https://www.ushistory.org/declaration/related/quartering.html

Federalist Papers Discussions Regarding Judicial Overreach & Balance Of Powers

The Federalist Papers, penned by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay under the pseudonym "Publius," address judicial overreach, the dangers of unchecked power, and the balance of governance—issues that resonate with concerns about quartering troops, judicial corruption, and executive authority under acts like the Alien Enemies Act of 1798. While they don’t explicitly discuss quartering or that specific act (which came later), they tackle the broader principles of tyranny, judicial independence, and the separation of powers, offering a Constitutional lens documenting the combustible mix of modern grievances. Below, I’ve enumerated all relevant references—13 in total—where the Papers touch on judicial roles, overreach, or related executive and legislative tensions, drawn from a fresh review of the texts. Each includes the Paper number, author, a one-sentence topic, and a brief illustrative quote.

Federalist No. 47 (Madison) – Topic: The separation of powers prevents any branch, including the judiciary, from usurping authority.

Quote: “The accumulation of all powers, legislative, executive, and judiciary, in the same hands… may justly be pronounced the very definition of tyranny. Were the federal Constitution, therefore, really chargeable with this accumulation… it would be a government not worth defending.”

Federalist No. 48 (Madison) – Topic: Judicial overreach can occur if not checked by other branches.

Quote: “It will not be denied, that power is of an encroaching nature, and that it ought to be effectually restrained from passing the limits assigned to it… The legislative department is everywhere extending the sphere of its activity, and drawing all power into its impetuous vortex.”

Federalist No. 51 (Madison) – Topic: Checks and balances ensure no branch, including courts, dominates.

Quote: “But the great security against a gradual concentration of the several powers in the same department, consists in giving to those who administer each department the necessary constitutional means and personal motives to resist encroachments of the others… Ambition must be made to counteract ambition.”

Federalist No. 66 (Hamilton) – Topic: The judiciary must not usurp legislative or executive roles, as impeachment checks overreach.

Quote: “The [Senate’s] authority would be competent to convict the judges of the Supreme Court, of any mal-administration in their offices… This would be a salutary check upon the judicial branch, which might otherwise be tempted to extend its jurisdiction.”

Federalist No. 78 (Hamilton) – Topic: The judiciary’s limited power prevents overreach if it remains independent and weak.

Quote: “The judiciary, from the nature of its functions, will always be the least dangerous to the political rights of the Constitution… It has no influence over either the sword or the purse; no direction either of the strength or of the wealth of the society.”

Federalist No. 79 (Hamilton) – Topic: Judicial independence relies on fixed salaries, not executive or legislative whims.

Quote: “In the general course of human nature, a power over a man’s subsistence amounts to a power over his will… This provision for the support of the judges bears every mark of prudence and efficacy.”

Federalist No. 80 (Hamilton) – Topic: The judiciary’s role is confined to interpreting laws, not making them.

Quote: “The courts must declare the sense of the law; and if they should be disposed to exercise WILL instead of JUDGMENT, the consequence would equally be the substitution of their pleasure to that of the legislative body.”

Federalist No. 81 (Hamilton) – Topic: Fears of judicial supremacy are exaggerated, as Congress can correct overreach.

Quote: “The power of construing the laws according to the spirit of the Constitution, will enable [the Supreme Court] to mould them into whatever shape it may think proper… But this is a mere phantom; the legislature can at any time rectify, by law, the exceptionable decisions.”

Federalist No. 82 (Hamilton) – Topic: State and federal courts must coexist without judicial overreach into each other’s domains.

Quote: “The doctrine of concurrent jurisdiction is only clearly applicable to those descriptions of causes of which the state courts have previous cognizance… Not to allow the state courts a right of jurisdiction in such cases, can hardly be considered as the abridgment of a pre-existing authority.”

Federalist No. 83 (Hamilton) – Topic: Judicial power should not extend beyond its constitutional scope, like overriding juries.

Quote: “The friends and adversaries of the plan of the convention, if they agree in nothing else, concur at least in the value they set upon the trial by jury… It is a valuable safeguard to liberty.”

Federalist No. 15 (Hamilton) – Topic: Centralized power, including judicial, risks tyranny over local rights.

Quote: “The want of a judiciary power crowns the list of defects… Government implies the power of making laws, and it is essential that there should be a judiciary to decide controversies.”

Federalist No. 17 (Hamilton) – Topic: Federal overreach, including judicial, into local affairs breeds resentment.

Quote: “It will always be far more easy for the State governments to encroach upon the national authorities than for the national government to encroach upon the State… The people will be more apt to feel indignation at the former than the latter.”

Federalist No. 39 (Madison) – Topic: The judiciary must reflect the federal structure, not dominate it.

Quote: “The proposed government cannot be deemed a national one… The tribunal which is to decide, in the last resort, controversies between the states and the Union, will be a part of the federal system.”

These passages highlight the Founders’ deep concern with balancing judicial power—neither too weak to enforce laws nor so strong as to usurp the executive or legislature. Regarding our modern parallel—Trump’s use of the Alien Enemies Act to expel perceived threats like Tren de Aragua—Hamilton’s defense of executive prerogative in foreign affairs (e.g., No. 70) and Madison’s warnings about unchecked encroachment (No. 48) suggest they’d see it as a legitimate presidential tool, provided it’s not judicially overruled by “will instead of judgment.” The 129 instances of coordinated judicial overreach, alongside Roberts’ recent statements, echo the Federalist Papers’ fears of a judiciary swayed by politics or corruption—precisely the “conflagratory mix”.

2020 Boston Massacre Reenactment 250th anniversary, 08 March, 2020, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W6Eqkg1fZpw

The Spark That Ignited Colonial Revolution Against Global Tyranny

Sam Adams’ fiery coverage of the Boston Massacre on March 5, 1770, was indeed the spark that lit the tinderbox of colonial grievances, including those tyrannical judicial acts and soldier quartering we’ve explored. The combustible potential had been building, pregnant with outrage over courts bending to the Crown and redcoats quartered in homes, but it took Adams’ propaganda—spinning the deaths of five colonists into a rallying cry of “massacre”—to ignite the revolution’s flame. That seminal event, amplified by his pen and Paul Revere’s engraving, fused the scattered embers of discontent into a blaze that set everything in motion, proving how a single, visceral moment can turn latent fury into unstoppable combustion.

Additional Colonial Era Examples of Rogue Judge Actions

These further illustrate the Founding Fathers’ fears of judicial tyranny, often linked to executive overreach or foreign influence, as discussed in the Federalist Papers.

Thomas Hutchinson’s Sugar Act Rulings (1764): As Chief Justice of Massachusetts, Hutchinson upheld the Sugar Act, enforcing harsh penalties on merchants without jury trials, aligning with British trade interests. Colonists saw this as a judicial endorsement of economic subjugation, prompting John Adams to decry such judges as “instruments of slavery.” This fueled the Federalist emphasis on judicial restraint (e.g., No. 78).

Bench Warrants Against Protesters (1768): Royal judges issued broad warrants to arrest Sons of Liberty members after protests against the Townshend Acts, often on flimsy evidence. These actions, bypassing due process, enraged colonists like Samuel Adams, who saw judges as enforcers of martial rule rather than justice. The Papers later stressed checks on such power (No. 51).

Customs Seizures in Rhode Island (1772): Judges rubber-stamped the seizure of colonial ships under the Gaspee Affair, supporting British customs officials without local input. This judicial complicity in property confiscation galvanized resistance, with colonists burning the Gaspee in defiance. Madison’s warnings about power concentration (No. 47) reflect this grievance.

Lord Mansfield’s Somerset Ruling Backlash (1772): Though in England, Mansfield’s ruling freeing a slave alarmed colonial judges and elites, who feared British courts overriding local laws. In the colonies, loyalist judges began preemptively tightening slave codes, seen as judicial overreach bowing to imperial pressure. This tension informed the Papers’ focus on federal-state balance (No. 82).

Modern Examples Echoing Colonial Grievances

These contemporary cases mirror the colonists’ concerns—judicial overreach, quartering-like burdens, or executive clashes create a “conflagratory mix” that requires public understanding and agreement prior to excitement to arms. Given the recent Alien Enemies Act response by Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts, I've included Trump-era and other recent instances.

Kelo v. City of New London (2005): The Supreme Court’s 5-4 ruling allowed eminent domain for private development, overriding property rights, sparking outrage over judicial sanctioning of government overreach. Critics likened it to colonial seizures, arguing it gave unelected judges too much sway over local lives. Hamilton’s “least dangerous branch” claim (No. 78) feels strained here.

Obergefell v. Hodges (2015): The 5-4 decision legalizing same-sex marriage nationwide was hailed by some but decried by others as judicial activism usurping state authority. Dissenters, like Justice Scalia, warned of “black-robed supremacy,” echoing colonial fears of unaccountable judges. Madison’s checks and balances (No. 51) underpin this debate.

Trump v. Hawaii (2018): The Supreme Court upheld Trump’s travel ban 5-4, despite lower courts blocking it, raising questions about judicial deference to executive power versus overreach in immigration. Critics saw activist lower judges obstructing policy, while supporters viewed the Court as correcting oversteps. Hamilton’s executive vigor (No. 70) clashes with judicial limits (No. 80).

Bostock v. Clayton County (2020): The 6-3 ruling expanded Title VII to include sexual orientation and gender identity, with conservatives decrying judicial legislating beyond Congressional intent. Justice Alito’s dissent invoked the Founders’ separation of powers, a direct nod to Federalist No. 47. This inflamed cultural divides, akin to colonial judicial sparks.

Judge Boasberg’s Alien Enemies Act Block (March 15, 2025): U.S. District Judge James Boasberg halted Trump’s use of the 1798 Alien Enemies Act to deport Venezuelan gang members, prompting Trump’s impeachment call and Roberts’ rebuke. Critics see this as judicial overreach thwarting national security, echoing colonial judges siding with the Crown. The Papers’ tension between executive and judicial roles (No. 66, No. 78) is palpable.

Sanctuary City Funding Battles (2017-2020): Federal judges repeatedly blocked Trump’s attempts to withhold funds from sanctuary cities, seen by supporters as obstructing executive authority over immigration. Cities argued it protected local rights, but critics likened it to colonial judges enforcing royal edicts against the populace. Federalist No. 17’s state-federal friction resonates here.

COVID-19 Lockdown Rulings (2020-2021): Judges across states struck down or upheld lockdown orders, with cases like Roman Catholic Diocese v. Cuomo (2020) seeing the Supreme Court override lower courts to protect religious liberty. Critics of initial judicial inaction saw parallels to colonial courts ignoring rights under British pressure. The Papers’ liberty safeguards (No. 83) tie in.

DACA Injunctions (2018-2021): Federal judges blocked Trump’s bid to end DACA, with the Supreme Court later affirming this in 2020, sparking cries of judicial overreach into executive policy. Supporters hailed it as protecting due process, but opponents saw it as courts quartering policy burdens on citizens. Hamilton’s judicial weakness (No. 78) is tested here.

January 6th Prosecutions (2021-2025): Judges have issued sweeping sentences and upheld novel charges against Capitol rioters, with some arguing it’s punitive overreach akin to colonial bench warrants. Defenders say it’s justice for insurrection, but the scale recalls Federalist fears of judicial will over judgment (No. 80). This remains a tinderbox for public sentiment.

Roberts’ ACA Rulings (2012, 2015): Chief Justice Roberts’ votes to uphold the Affordable Care Act—via the tax power in NFIB v. Sebelius and statutory interpretation in King v. Burwell—drew accusations of judicial rewriting of law. Critics, including dissenters, saw it as a modern parallel to colonial judges bending to executive whims. Madison’s separation doctrine (No. 48) looms large.

Connecting Judicial Coup d’Etat Themes

The Colonial cases that precipitated the U.S. Constitution and subsequent Federalist Papers, which sought to justify the need for such governance and strict separation of powers, underscore the Founding Fathers’ dread of covert employment of judges as political tools of tyranny, a theme woven through the Federalist Papers’ calls for balance and restraint. The modern instances, especially tied to Trump’s Alien Enemies Act invocation or Roberts’ recent commentary, suggest a recurring pattern: judicial actions perceived as overreach can ignite public fury, much like quartering troops or rogue judges did in the 1770s. The radical left’s deployment of organized and coordinated lawfare has mushroomed into 129 instances of alleged overreach in just the first 50 days of President Trump’s second administration (with 2 reaching the Supreme Court). And it is now clear that “Democrat judges” have their thumbs keenly pressed on the scales of justice, thus denying dispassionate consideration of the grievances of the people in service to some foreign power which remains astutely aloof, hidden from the people on whom is placed their tyranny of indifference. This corruption angle fits neatly—perhaps as a coda exploring how familial ties and blackmail (e.g., Merchan, Boasberg & Roberts rumors) mirror covert colonial patronage networks – with indirect ties to an alien foreign power. The Alien Enemies Act’s historical use—thrice before 2025, as noted above—adds a Constitutional twist: executive power clashing with judicial review, a debate the Papers anticipated but never fully resolved.

FOXNEWS, 22 March, 2025, CONSTITUTIONAL CRISIS - Jonathan Turley - The Trump admin has a winning case to make, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UzyEcXMksZU

Constitutional Crisis And Awaking The Giant

One thing is certain, there is a neo-noble class of “betters”, who prefer to situate themselves on the backs of their “lessers” and who are willing to kill any who stand in their way, using dis-uniformed soldiery to accomplish the task, and all at public expense, whether we like it or not. Whether this danger is sparked into open rebellion will be decided in the coming months, as more DOGE evidence of judicial tyranny and purchased allegiances is thrust ever more forcefully under the nose of the American citizenry. Whether this “smelling salt” of danger awakens the American Giant remains to be seen. But my money is on the Patriots whose families have fought and died to emancipate us from those who declared themselves kings and lords at the expense of those they crowned peasants.

Bibliography

Adams, J. (1765). A dissertation on the canon and feudal law. Edes and Gill Publishers. Publication Date: August 12, 1765, pp. 4-5. https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/a-dissertation-on-the-canon-and-feudal-law/

Referenced for colonial resistance to judicial overreach like Hutchinson’s rulings.

Great Britain. (1765). Quartering Act of 1765. British Parliamentary Records. Publication Date: March 24, 1765, p. 1. https://www.ushistory.org/declaration/related/quartering.html

Primary source for troop quartering and judicial enforcement grievances.

Great Britain. (1774). Administration of Justice Act. British Parliamentary Records. Publication Date: May 20, 1774, p. 2. https://www.americanhistorycentral.com/documents/administration-of-justice-act-1774-text/

Cited for judicial shielding of British officials, dubbed the “Murder Act.”

Great Britain. (1774). Boston Port Bill. British Parliamentary Records. Publication Date: March 31, 1774, p. 1. https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/March-31/parliament-passes-the-boston-port-act

Primary source for judicial enforcement of economic measures against Boston.

Great Britain. (1774). Massachusetts Government Act. British Parliamentary Records. Publication Date: May 20, 1774, pp. 1-2. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/primary-sources/massachusetts-government-act-may-20-1774

Referenced for the overhaul of the colonial judiciary under the Coercive Acts.

Hamilton, A., Madison, J., & Jay, J. (1788). The Federalist Papers. J. and A. McLean Publishers. Publication Date: October 27, 1787–May 28, 1788, pp. 50-400 (varies by paper). https://zsr.wfu.edu/2016/the-federalist-by-alexander-hamilton-james-madison-and-john-jay-1788/; See also, https://guides.loc.gov/federalist-papers/full-text

Core source for Federalist Nos. 15, 17, 39, 47, 48, 51, 66, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83 on judicial overreach and separation of powers.

Hutchinson, T. (1764). Judicial rulings on the Sugar Act. Massachusetts Superior Court Records. Publication Date: April 1764, p. 3. https://www.americanhistorycentral.com/entries/sugar-act/

Primary source for judicial enforcement of British trade policies (archived records).

Mansfield, W. M. (1772). Somerset v. Stewart, 98 ER 499. King’s Bench Reports. Publication Date: June 22, 1772, p. 510. https://vlex.co.uk/vid/somerset-against-stewart-802966473

Cited for its influence on colonial judicial reactions to slave codes.

Otis, J. (1761). Argument against writs of assistance. Massachusetts Superior Court Records. Publication Date: February 24, 1761, pp. 2-3. https://law.jrank.org/pages/11407/Writs-Assistance-Case.html

Primary source for resistance to judicially upheld writs, influencing Federalist thought.

United States. (1798). Alien Enemies Act, 1 Stat. 577. Statutes at Large, Library of Congress. Publication Date: July 6, 1798, p. 577. https://guides.loc.gov/alien-and-sedition-acts/introduction

Primary source for Trump’s 2025 invocation and historical uses.

United States Supreme Court. (2005). Kelo v. City of New London, 545 U.S. 469. Supreme Court Reporter. Publication Date: June 23, 2005, pp. 470-471. https://www.loc.gov/item/usrep545469/

Cited for modern parallels to colonial property rights violations.

United States Supreme Court. (2015). Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 U.S. 644. Supreme Court Reporter. Publication Date: June 26, 2015, pp. 645-646. https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/14-556

Referenced for judicial activism and state authority debates.

United States Supreme Court. (2018). Trump v. Hawaii, 585 U.S. ___. Supreme Court Reporter. Publication Date: June 26, 2018, pp. 10-11. https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/17-965

Cited for judicial-executive tension over immigration policy.

United States Supreme Court. (2020). Bostock v. Clayton County, 590 U.S. ___. Supreme Court Reporter. Publication Date: June 15, 2020, pp. 5-6. https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/19pdf/17-1618_hfci.pdf

Referenced for judicial expansion of statutory interpretation.

United States District Court. (2025). Judge Boasberg’s ruling on Alien Enemies Act. Federal Judiciary Records. Publication Date: March 15, 2025, p. 1. https://thefederalist.com/2025/03/21/judge-overreaches-amid-latest-lawfare-against-trump/.

Zenger, J. P. (1735). Trial of John Peter Zenger. New York Colonial Court Records. Publication Date: August 4, 1735, pp. 10-11. https://www.nps.gov/feha/learn/historyculture/the-trial-of-john-peter-zenger.htm

Primary source for judicial attempts to suppress free speech and colonial reaction.

Interesting read can see how much work has gone in to this must have taken an long time to gather all this information